Peregrines

by Walt Anderson

I recognize that I am a peregrinator—a wanderer—as I have led nature expeditions in many parts of the world. Everywhere I have gone, except Antarctica, hosts the Peregrine Falcon, the most widely distributed raptor in the world. The Peregrine is the epitome of speed and power in flight, capable of dives (stoops) of over 200 mph. It is the fastest member of the animal kingdom, though when it comes to velocity in relation to body size, a tiny mite that can zoom along at 322 body lengths per second takes the prize. The Peregrine is fast even by that standard, as it has been clocked at 186 body lengths per second. Relative to size, that mighty mite, the Anna’s Hummingbird, puts all other birds to shame.

Peregrines tend to seek relief: vertiginous cliffs, in particular. Cliffs provide suitable nesting spotsusually in a small cave or beneath an overhang—where the nest and nestlings are relatively safe from predators, though those tigers of the night, Great Horned Owls, do take chicks and even adults at night. On many occasions, I have watched Peregrines screaming and diving at owls discovered during the daytime. These species are the avian equivalent of oil and water, almost as antagonistic as our political parties today.

Usually I look for Peregrines around cliffs or bodies of water where there may be abundant potential prey. One May day to my great surprise, I sensed the sudden arrival of a shape right outside my study window. Imagine my shock when I saw it was a wild Peregrine! Apparently, it had chased a bird under the deck, as it was watching intently, ignoring me completely as my camera fired shot after shot through my closed window.

Notice the long, pointed (falcate) wings and the long toes with wickedly sharp talons. A very talonted bird!

As diurnal birds of prey, falcons were long thought to be related to hawks, eagles, kites, harriers, and accipiters—the family Accipitridae. It turns out that they aren’t related at all apart from being birds. The family Falconidae is much closer genetically to parrots and songbirds! The similarity is another case of convergence—similar appearances that were selected for to suit similar lifestyles. It should remind us not to jump to conclusions—appearances can be deceiving.

This same wild Peregrine that landed on my deck shows large eyes (outstanding binocular vision), sharply hooked beak with a notched tooth (useful for severing the neck vertebrae of its prey), fleshy yellow cere with a circular nostril and bony tubercle inside (apparently helps it deflect wind so the bird can breathe effectively during those dramatic, high-speed stoops). The broad moustachial stripe is another field mark of a Peregrine.

Peregrines are highly territorial toward others of their kind, and that may help reduce competition for prey. They tend to avoid flat plains, extreme deserts, and dense rainforest areas. Peregrines have been known to catch prey as small as a hummingbird and as large as a heron or crane. Prey items in North America include more than 300 species of birds. Most common prey, however, are birds around the size of a pigeon or dove, though the falcons readily take shorebirds and waterfowl (in the NE United States, they were known as the Duck Hawk). In areas with plenty of bats, they often are crepuscular, hunting at dawn and dusk for those yummy volant mammals.

Being at the top of the food web, however, has its own challenges, and when DDT was being sprayed all over the country in the mid-20 th Century, Peregrines and many other top consumers accumulated chemical toxins to the point where their eggshells were so thin that they collapsed under the bird’s weight. The Peregrine was one of the first listed as Endangered in 1969, and their prospects were dim until DDT was banned. Serious restoration efforts led by the Peregrine Fund brought them back to a healthy population. They were downlisted from Endangered in 1999, one of the most notable conservation success stories of our country.

The Peregrine is highly prized by falconers, so much so that among the Western European aristocracy, it was considered the prince of birds (the Gyrfalcon of the Arctic was the “king”). Falconry is an ancient sport, dating back three millennia. Falconer and falcon become tightly bonded, so this sport requires extreme commitment.

The Granite Dells of Prescott is perfect Peregrine habitat with incredible cliffs and proximity to Watson and Willow Lakes, where plenty of waterbird prey are available.

I was at Watson Lake one day when I heard this feathered missile collide with its prey, an American Coot. I turned around and watched for a half hour as the fearless bird plucked the unlucky coot until it reached satiation. Just a couple days ago, I found a freshly headless coot in the canyons of the Dells, with a Peregrine circling above. It had just been scared off its prey by a car that came along at the wrong time. Peregrines have incredible speed and agility in the air, and it is common for them to strike the flying prey with a closed fist such that the victim falls to the ground and is collected by the hunter. Smaller birds are snatched right out of the air with those long talons.

The Prairie Falcon is found in open country throughout the US West and Mexico. It is easily distinguished from the Peregrine by its pale sandy colors, narrow moustache, and black “wingpits” (axillars) in flight. It catches most of its prey (ground squirrels, meadowlarks, etc.) on the ground.

Perfect habitat for a Peregrine, here seen middle-left above the goldenbushes (Ericameria cuneata). Its preference for cliffs has led to some of them becoming birds of the skyscrapers, nesting on high-rise ledges and feeding on feral Rock Pigeons. Chicago has honored the species as the official city bird! How ironic that this symbol of wilderness now thrives in the vertical canyons of some of our biggest cities.

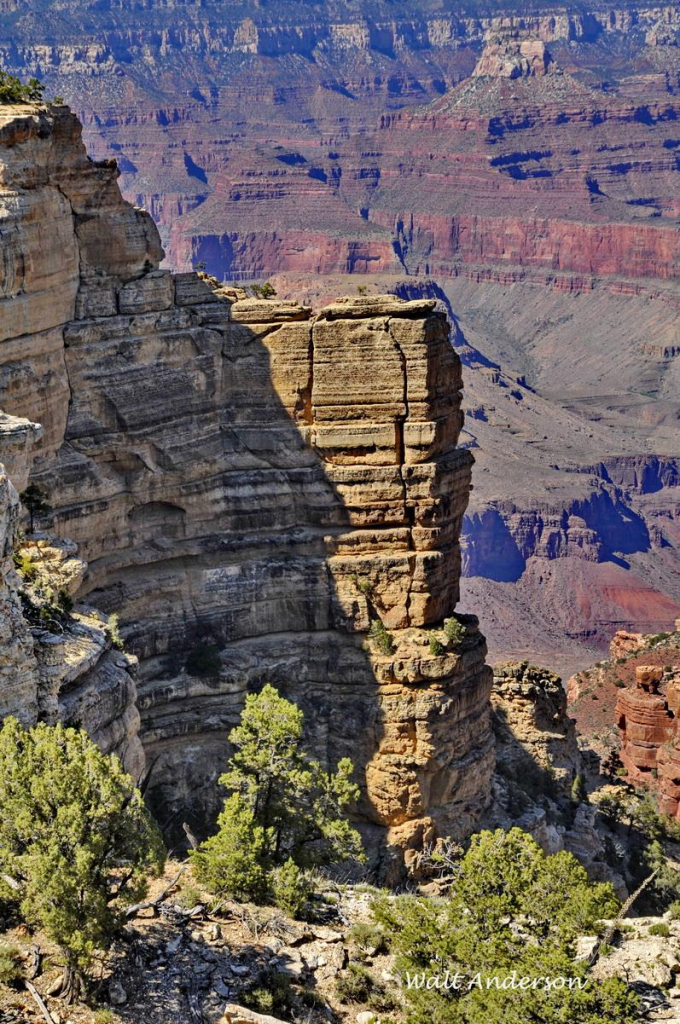

The Grand Canyon has the highest breeding population of Peregrines in the state of Arizona, and no wonder. Cliffs, needles, and spires abound. The canyon also is home to a recovering population of the endangered California Condor. Migratory raptors also fly through the canyon, making this a prime hawkwatching site. It’s important to recognize that the Grand Canyon is far more than mere (albeit grand) scenery; it is a vast wilderness where many ecological dramas play out daily.

Good morning, I am currently passing thru Buenos Aires, fairly suee i saw a Peregrine close by the main station. My home is in Dublin Ireland and each day on my morning walk up Killiney Hill I hear the sound of a Peregrine there but seldom catch a glimpse. Last year, while climbing Camelback Mountain, AZ, having wheezed my way to the top, i observed a Peregrine in a full stoop! The second time i had ever witnessed….. The first being on The Burren in Co Clare, West of Ireland some 12 years ago.