Alligator Juniper

by Walt Anderson

One of the most distinctive trees of the Southwest is the Alligator Juniper, well-named for its platy, saurian-like bark. My natural history students had no trouble learning it by appearance, and, with the mnemonic clue, “Johnny Depp,” they quickly caught on to its scientific name, Juniperus deppeana. Of course, an organism is so much more than its name, and the Alligator Juniper is special in so many ways that it earns the limelight in this essay. As you will see, this amazing plant is one of my all-time favorites, very close to my heartwood.

Though it is very slow-growing, the Alligator Juniper can be quite long-lived—perhaps up to 800 years. Old specimens have the characteristic platy bark and often areas of dead wood, indicative of stresses they have lived through. Here it has become a fancy planter for a Claret-cup Cactus.

This ancient tree shows the “striping” of bark distinguishing dead areas (where lichens can grow) and the vibrant scaly bark connected to the living foliage. Like manzanita, this juniper can sacrifice limbs and continue to live. This growth pattern certainly adds to the rustic charm and character of an old-growth juniper. This is the largest of all our juniper species. It is found from the Mogollon Rim in Arizona over into New Mexico and down through the sky islands region well into Mexico.

It tends to live at higher elevations than Utah and One-seed Junipers, though there is some overlap. Rarely is it in such a pure, essentially monotypic stand as this one near Prescott’s Granite Mountain. More often, it is a scattered element in woodlands or forests with oaks and pines.

It’s not abundant in Prescott’s Granite Dells, but it definitely adds character where it occurs. There is something very magical about a twisted tree anchored in rocks, persisting for centuries in a harsh but beautiful setting like this.

Mature trees were often cut, in whole or in part, by settlers and ranchers for fence posts, mine timbers, firewood (it burns hot!), railroad ties, or even decorative furniture. Native Americans used the wood as supports in pueblos and hogans, for fencing, for medicinal practices, for food flavorings, and as ceremonial incense.

Juniper foliage consists of overlapping scales, though young sprouts often have much sharper, pointed needlelike leaves. Close inspection reveals whitish glands.

Alligator Junipers are typical dioecious (“two houses”), with separate male and female trees. Males produce prolific pollen (sometimes filling the air with yellow powder that creates a golden film on still water where it lands). Though I love these trees, they obviously don’t love me, as I suffer severe allergic reactions to the pollen when it is abundant in February and March. All right, I know they aren’t intentionally making me miserable. Pollen is just one half of the reproductive process, and without it, we wouldn’t have junipers.

Females produce fleshy “berries” (cones in which some soft and thick scales have fused). The fruits are important foods for foxes, coyotes, skunks, robins, thrushes, bluebirds, and many other species. Because of limited terrestrial mobility for mammals and quick digestive passage for birds eating juniper berries (in and out in about 12 minutes for a solitaire), seed dispersal does not occur over great distances, a serious potential problem prohibiting significant range shifts as global warming changes local conditions. See Connie Barlow’s predictions and her story of how we may have to help this species out as climate change advances: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kbyx2eKUv-Y

Deer and elk can eat the winter foliage, which is a bit more palatable to them than the leaves of other junipers. This juniper was hit by a February snowstorm, very much like the one that is occurring outside as I write these words.

The fruits typically have a whitish “bloom.” Once in a great while, you find an individual Alligator Juniper that has both male and female flowers present—monoecious (“one house”). Mother Nature has plenty of examples of non-binary individuals, and this is the sort of evolutionary diversity we should welcome.

Fire can kill mature trees, though the bark offers some protection if the fire is not too hot.

On June 18 of 2013, careless target shooters to the south of Granite Mountain started what became known as the Doce Fire, which swept north at incredible speed, racing over the mountaintop and down to the edge of a residential area in Williamson Valley. The 20-man Granite Mountain Hotshots team was aware of the ancient alligator juniper that grew in view of the mountain for centuries. Revered and respected, that tree stood in the line of fire. But for the intervention of the hotshots, it might today be nothing more than a lifeless, charred trunk, victim of one fire too many. The crew saved it by creating firebreaks and by using their personal water containers to put out spot fires in its branches. This was an act of thoughtful heroism; these men put themselves on the fire line simply to save a tree.

But it was, and still is, more than a tree—it is a symbol of resistance, of fortitude, of ancient wisdom. In other words, it stands for values we admire and care about. It was the tree, not a tree. And it survived.

Twelve days after the Doce Fire, the hotshots were deployed to fight the Yarnell Hill Fire. I was at the Doce site and saw the plume of smoke to the south and knew instantly that Yarenll was in the path of a new fire. I raced down there and watched two horrific firenados merging, collapsing with burning brands that started smaller fires everywhere. Nineteen of the twenty Granite Mt. Hotshots died in one of the worst wildfire disasters in the state’s history.

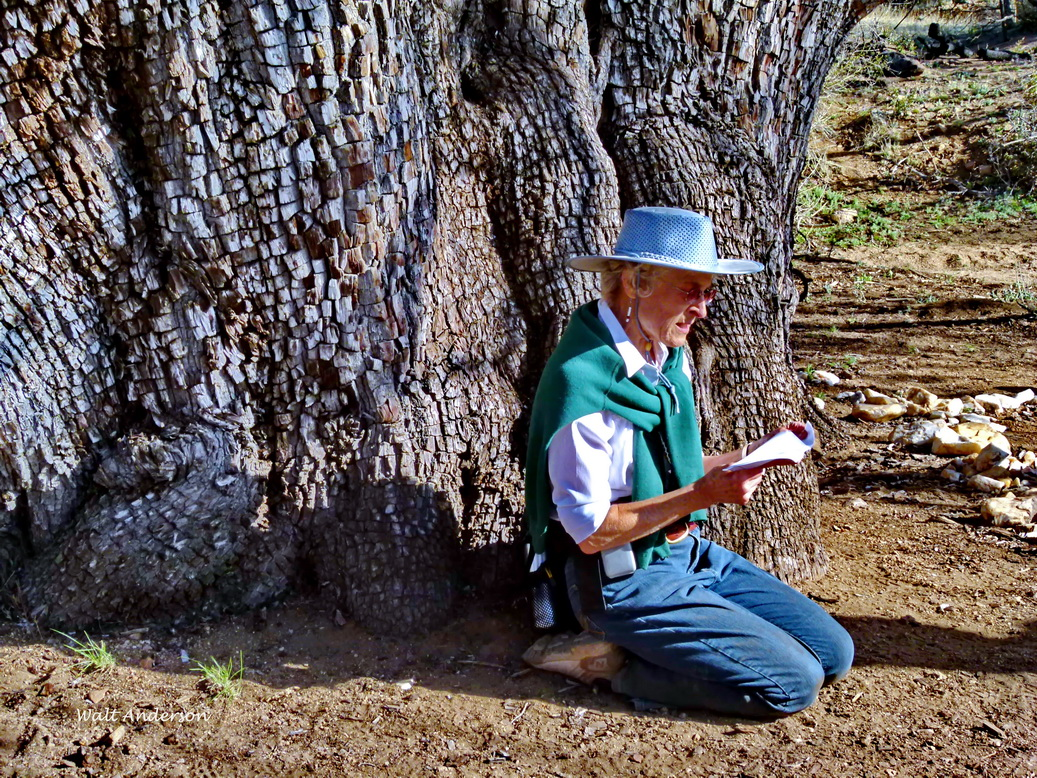

On April 13 of 2014, I guided a large group of interested folks, devoted pilgrims really, to the site of the ancient juniper that the hotshots had saved. The fire had killed every tree on the north side of the giant tree and would likely have killed it.

Here Doug Hulmes, Prescott College professor and champion of sacred trees, explained how he and a group of students from Norway chanced to encounter the sole surviving member of the Granite Mountain Hotshots at this very tree not long ago. Then Bethany Hannah, herself a hotshot firefighter, spoke of the obvious care that the GM Hotshots took when they built their firebreaks. The evidence denotes real respect and caring.

The ceremony began, led by Connie Barlow (champion of assisted migration as a strategy to save tree species that could be stranded by the effects of global warming) and Michael Dowd (evolutionary theologian and author of Thank God for Evolution). We listened, grieved, and remembered. It was one of the most powerful ceremonies I have ever experienced.

Then we approached the tree, massive at its base and spreading its huge branches out laterally farther than it is tall. We touched its rough bark, witnessed its many scars, even embraced the trunk lovingly. Joan Dukes read a remembrance; she first visited this tree over forty years ago. Forty years is significant in human scale, but a moment in the lifespan of this tree.

This ancient tree had beaten the odds. Most of the berries that junipers produce are eaten by mammals or birds or fall where there is no hope of germination or long-term survival. Fires inevitably occur, and wood is inherently combustible. This singular juniper that so impressed and inspired us is a one-in-amillion survivor. How many of the younger trees and saplings nearby are its offspring? Eventually it will die, and its genetic legacy will live on in its offspring … as long as the climate does not shift too far, Connie would remind us.

The cultural legacy of this impressive alligator juniper depends on us. We will need to pass on its story, generation after generation, or that will disappear as surely as wood rots into the ground. So too the Granite Mountain Hotshots. Their story also depends on us. May we never forget.

If one of the ancient ones dies, it is quite literally toast. Smaller ones may survive by sprouting from the base. This is an important evolutionary response to living in a fire-prone ecosystem.

A fire near Thumb Butte killed many branches, but this juniper sprouted from adventitious buds on its trunks. Every other plant in this landscape had to start from the ground up, oaks from basal sprouts and manzanitas from germinating seeds.

When the Granite Dells was hit by that hailaceous storm in July of 2021, all foliage was pulverized and gone. Both Ponderosa and Pinyon Pines had no way to compensate for complete needle loss, and they still look dead in February 2022. However, this Alligator Juniper photographed on 18 February 2022 shows vigorous sprouting from what are known as epicormic buds.

I should join my non-epicormic buds at the local brewery to ponder this phenomenon.

The Alligator Juniper was first collected and named by Dr. Samuel Washington Woodhouse of the Sitgreave’s expedition in 1851. He is the Woodhouse for whom this Woodhouse’s Scrub-Jay was named. Alligator Junipers are wonderful wildlife habitat. In mast years when the trees are loaded with berries, bird densities can be up to 70% higher than in non-mast years. It’s just another example of boom-and-bust economies in the Southwest!

Over thirty years ago, I did a series of watercolor paintings of birds of the Sky Islands of SE Arizona, and one of my favorites featured Acorn Woodpeckers doing a “flash dance” on an ancient Alligator Juniper.

Thanks for joining me today for some stories of a fascinating tree. The big unfolding story right now is what will happen to our trees in the next 30 or 50 or 100 years. Ecologists are modeling different scenarios, and each tree’s story will be different. However, if future generations are to experience and enjoy some of the most vulnerable species, it will require good predictive models and conscious adaptation, perhaps using assisted range expansion to deal with it.

That was an especially nice essay on the alligator juniper. I was able to admire them last week, as we hiked in the Dragoons, up to Stronghold Pass. I also enjoy the stand in Bonita Creek campground area of the Chiracahuas. Home to many acorn woodpeckers.

Thanks for letting yourself include the two fires, what the hotshots did for the tree, mention of those who died, and also the non-binary tree acceptance words. Heartening writing, for person, beast, and plant.

Perhaps you have more tree essays in the works. Great photos, fine writing, what a delicious thing to take in as i sip my morning tea.

Thank-you

Holly, thank you for the kind words. Yes, I will sprinkle in more tree essays among those featuring other taxa, and I will send you some reading through your email address..

Are you the Walt Anderson who at one time lived on Malheur National Wildlife Refuge?

👏 Thanks… I came in search of a possible allergen culprit and I think I found it. My new home near Show Low has many of these trees and yesterday I noticed the wind swept a huge sheet of pollen up into the air. I thought it was dust. But now that I know the source, my stuffy nose is worth it.

Yes, Mark, this is juniper pollen season! Take care!

I have a Juniperus deppeana behind my home that someone estimated to be 400 years old. It is about 2 stories high and only has living branches on the top 20 feet , except for 1 small branch 11 ft. Up. The circumference of the trunk at it’s base is 84 in. I would love for you to see it. I live in Lakeside AZ in the summers.

Thanks for the interesting article and photos. Do you know how small seedlings May transplant? I am planting five small seedlings today taken from private property near Quemado New Mexico. They are being planted just 7 miles east of the Greenhorn mountains near Rye, Colorado.