by Walt Anderson

My recent post on Wood Ducks featured one of the most beautiful of the waterfowl, though the entire family has many devoted fans, except perhaps the golfers who hate geese on the fairways. In contrast to the popular Anatidae, the Rallidae (rails, coots, gallinules) may be the Rodney Dangerfields of the water birds, not getting much respect. We shouldn’t deride the rails! I hope to improve their reputations a bit with this Wild Wednesday.

There are 143 species of rallids worldwide, but only 9 native species in North America and a half dozen in Arizona, not counting accidentals. I will cover the American Coot, Common Gallinule, and Sora in this account.

Monday was World Water Day, and we in Arizona should value water above almost any other “resource,” though our track record is not good. We have destroyed over 90% of the state’s natural wetlands, and that number will continue to rise as we pump groundwater from our aquifers.

Arivaca Cienega, the best rallid habitat on the refuge, was nearly lost to development, which would have had condos and likely a golf course. While coots love the short grass of a golf course and compete for space with the old coots in the golf carts, we can be grateful that the sale to a developer was averted and the cienega is now protected.

We need to start “thinking like a watershed.” Preserving open spaces, reducing pollution in our creeks and reservoirs, and minimizing water use at home and in our industrial areas can help, but we also need to think about the value of surface water and wetlands (including riparian areas with cottonwoods, willows, ash, and the like) to our native wildlife.

Mars is proof enough; we cannot have a world without water.

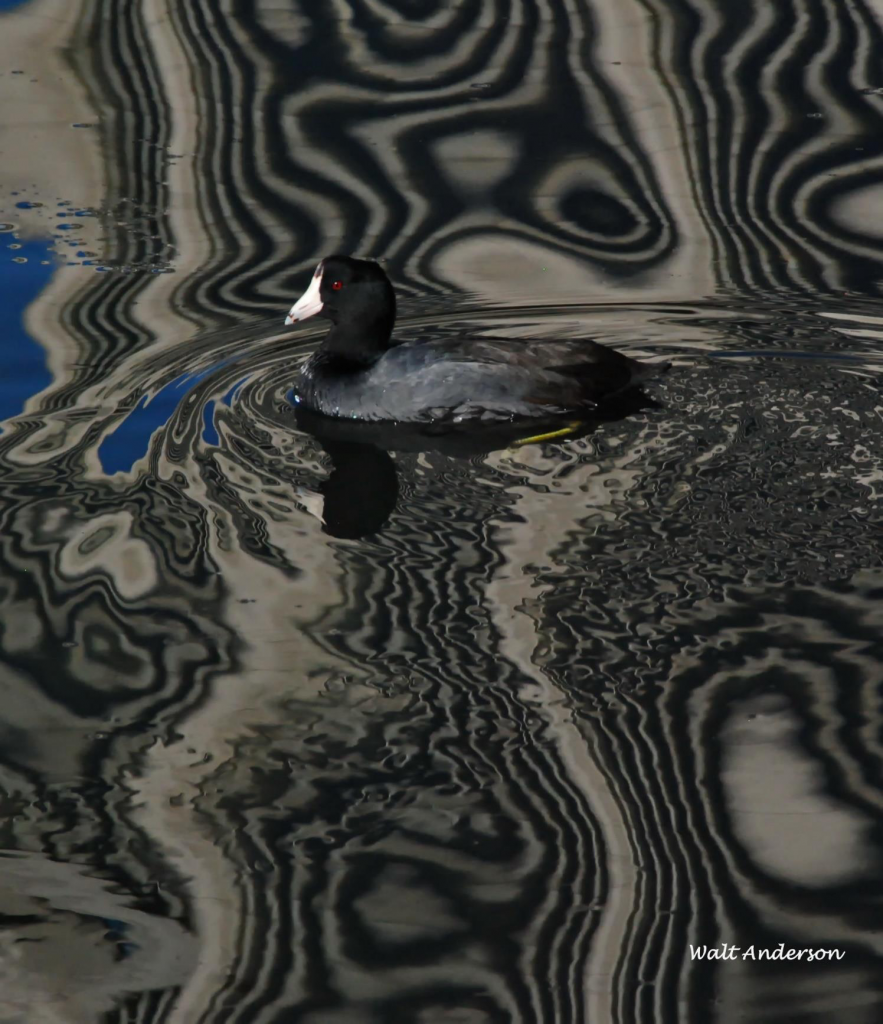

The coot is by far the most familiar of the rallids, though I am amazed at how many people think it’s an ugly duck. I found this one swimming on a liquid zebra. Well, actually, these were reflections of tall buildings along Lake Merritt in Oakland, California. I think it merits a photo. It does show that coots are highly adaptable—just add water.

∙∙∙

Stubby-winged coots are not great flyers; if an eagle passes overhead, they patter frantically across the water, often giving up before becoming airborne.

∙∙∙

But they can fly good distances while migrating, though they do it at night when no one can watch! In Arizona, although some breed in our remaining natural or artificial wetlands, most come through on migration, and they can form very large flocks on open bodies of water.

∙∙∙

Coot-watching is actually quite fun, as they are very vocal and demonstrative. Their konks, croaks, grunts, and cackles, often while head-bobbing as they swim along, can be hilarious to listen to, but they are meaningful in coot communication.

∙∙∙

Coots are territorial and aggressive toward one another. The one on the right is approaching with threatening intent. If his rivals don’t swim away, he may attack, and sometimes a couple rivals will fight face-to-face with feet locked together and beaks jabbing.

∙∙∙

But coot pairs can be surprisingly affectionate, and they are dedicated parents. Both sexes incubate (the female does lay the eggs), with the male often taking longer sitting bouts than the female. As the chicks hatch over a period of several days, the parents each take a few of the brood and feed them aquatic plants and insects for up to 70 days after hatching. The chicks are semi-precocial, so they can swim, but they depend on their parents for those weeks even as they are learning to forage for themselves. The adults also guard them and drive away even innocent neighbors, like a family of teal. Though the teal are not a direct threat, they might compete for food, so the coots won’t tolerate their presence near their brood.

A chick is bizarrely unlike an adult, with a bright red bill and bald red cap, black mask, and a conspicuous neck ruff of downy yellow-orange feathers. Though it makes them conspicuous, this apparently is selected for attracting parental attention and favoritism. Experimenters have reduced the ornaments and discovered that parents are turned off, neglecting the less flamboyant chicks. Sad to think about.

∙∙∙

A close look at a coot shows it doesn’t have the depressed beak of a duck. The beak continues up on the forehead to create a “frontal shield,” which may be useful in courtship. As they forage by day and migrate at night, it should not be surprising that they have red eyes. It’s also not surprising that I would make that joke.

∙∙∙

The Common Gallinule (which used to be called a Moorhen and still is in Europe and Africa) is less well known than its cootly cousin, as it is more timid and usually stays within or very close to dense marsh vegetation. It is an opportunistic omnivore, dining on insects, snails, and aquatic plants. Its candy-corn beak has a frontal shield, even more pronounced than that of a coot. “Frun- tall- sheeled”—yes, it is pronounced.

∙∙∙

Gallinules are cooperative breeders, in that the young from the first clutch may chip in to help take care of their younger siblings from the second clutch. That’s why they are called “clutch performers.”

Note the long toes that are helpful for it to clamber around on floating or emergent vegetation. In fact, the feet grow faster than other parts of the body so that chicks can get around more easily. I’m impressed with those red “gaiters” though I have no ready explanation for their function.

∙∙∙

Compare the gallinule’s long toes with the lobed toes of coots, which they use to help them swim. They close the lobes on the forward stroke and expand them to push against the water, an effective alternative to the webbed feet of ducks. Lobes are also found on the toes of unrelated phalaropes and grebes, a good example of convergent evolution.

∙∙∙

Even without webs or lobes , gallinules and other rails can swim when they want to.

∙∙∙

The Sora is a shy, secretive, reclusive rail. One description is “somewhat retiring,” which I can relate to, as I am somewhat retired. I’ve seen plenty of Soras, usually briefly as they venture out from the cattails, snatch some food, then dash back into the marsh vegetation. I more often hear their wild descending, squealing whinnies or whistled “kooee” calls. These are the mostly widely distributed of North American rails (one might call them transcontinental rails).

∙∙∙

Some rails (not this fat one) are laterally compressed to move easily through dense emergent vegetation (hence the phrase, “as skinny as a rail”). Most rails are highly dependent upon thick marshy vegetation, which has disappeared across many parts of their range. In my opinion, those who drain marshes are Sora Losers.

∙∙∙

There are many more stories I could tell about the coot, which has become a favorite of mine. Some people disparage them, calling them Mudhens, Pulldoes, and worse. All right, it is not an elegant, graceful bird, as this photo shows. But I think they deserve a more dignified name, perhaps something like Ivory-billed Mudpecker. One in the wild lived to the age of 22 years and 4 months, an old coot indeed. I will accept that term as endearment if it is applied to me.

I just discovered your posts here on Friends of BANWR. Great writing, at turns educational and humorful. Perfect with my morning tea. I love especially how water patterns and reflections enhance an excellent bird image. Beautifully done.

Signed,

Holly, fellow Oregonian (and Oro-Valley-ian in winter).