by Walt Anderson

The Hairy Woodpecker has one of the largest ranges of any North American bird. In fact, it is found in forested areas from Alaska to Panama. This bird is striking in more ways than one, so let’s take a closer look at this common neighbor of ours.

Almost anyone can recognize a woodpecker, the only good kind of chiseler. Their basic body plan is pretty similar within the family: 224 species found around the world. That powerful, chisel-like bill is the most distinctive feature, though there are plenty of anatomical similarities to clinch the deal. The Hairy gets its name from the filamentous feathers in that white cloak on its back.

The male Hairy Woodpecker has a red crown that the female lacks, and there are some differences in foraging behavior between the sexes, but both male and female are heavily invested in parental care. Monogamy is normal, as it takes both sexes to successfully incubate (the males does so at night) and raise the young. Each sex is territorial against others of the same sex; hanky panky is thus rare compared to the “sneaky” behavior of many songbirds. Through his diligent paternal efforts, the male avoids being hen-pecked. . . . Just look at that honkin’ beak! No diminutive Downy here!

The female lacks the red crown of the male. Beginning birders often mistake them for the smaller Downy Woodpecker, which has a smaller beak and black bars on the white outer tail feathers. A useful mnemonic is that Hairy is Huge and Downy is Dainty. They are so similar that for many years, they were thought to be close cousins, but DNA evidence says that they diverged from a common ancestor about 6.5 million years ago and are NOT each other’s closest relative.

The Hairy’s closest relative is actually the Arizona Woodpecker, which has heavily spotted and barred underparts and a brown back without a white cloak. It’s typically a bird of the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico, just getting up into the Sky Islands of SE Arizona. I photographed this cooperative bird this spring in Madera Canyon in the Santa Ritas south of Tucson. The Downy Woodpecker, on the other hand, is more closely related to the Nuttall’s Woodpecker of California and the similarly barred Ladder-backed Woodpecker of the SW (eastern California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and much of Mexico). In fact, Downy and Nuttall’s Woodpeckers have crossed their species lines to hybridize now & then.

This Arizona Woodpecker shows the powerful hammering that typifies a woodpecker after invertebrates in the bark. Don’t try this at home! You would expect such percussion to lead to concussion, but woodpeckers have a number of adaptations that avoid this. Their small brains (no offense implied, as they appear fairly intelligent) relative to head size are above the direct line of impact forces and have more surface area relative to volume, thus receiving much less force on the brain than we would if we did this. Like other birds, they have less cerebrospinal fluid that would transmit dangerous shock waves. That powerful bill is also used in ways that minimize potentially dangerous shearing and rotational forces. In other words, wearing a helmet is not necessary!

The big question then is why are Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers so similar if they aren’t so closely related? Well, since they do share a distant ancestor, some traits may simply be conservative, not so subject to the forces of natural selection as some other features. However, both species have different races around the continent, and those races tend to be similar where they co-occur. The leading hypothesis is that they have plumage mimicry. That is, perhaps the small Downies are able to displace other birds from food sources by looking close enough at first glance to the more powerful and intimidating Hairy. There are other unrelated woodpecker species pairs around the world that also appear to have plumage mimicry, and geographic overlap is a better predictor of similarity than are genetics, habitat, or climate. Once again in nature, appearances can be deceiving!

In much of the West, Hairy Woodpeckers are closely associated with forests of Ponderosa Pines, though they do occur in some pinyon-juniper stands and up into mixed conifers at higher elevations.

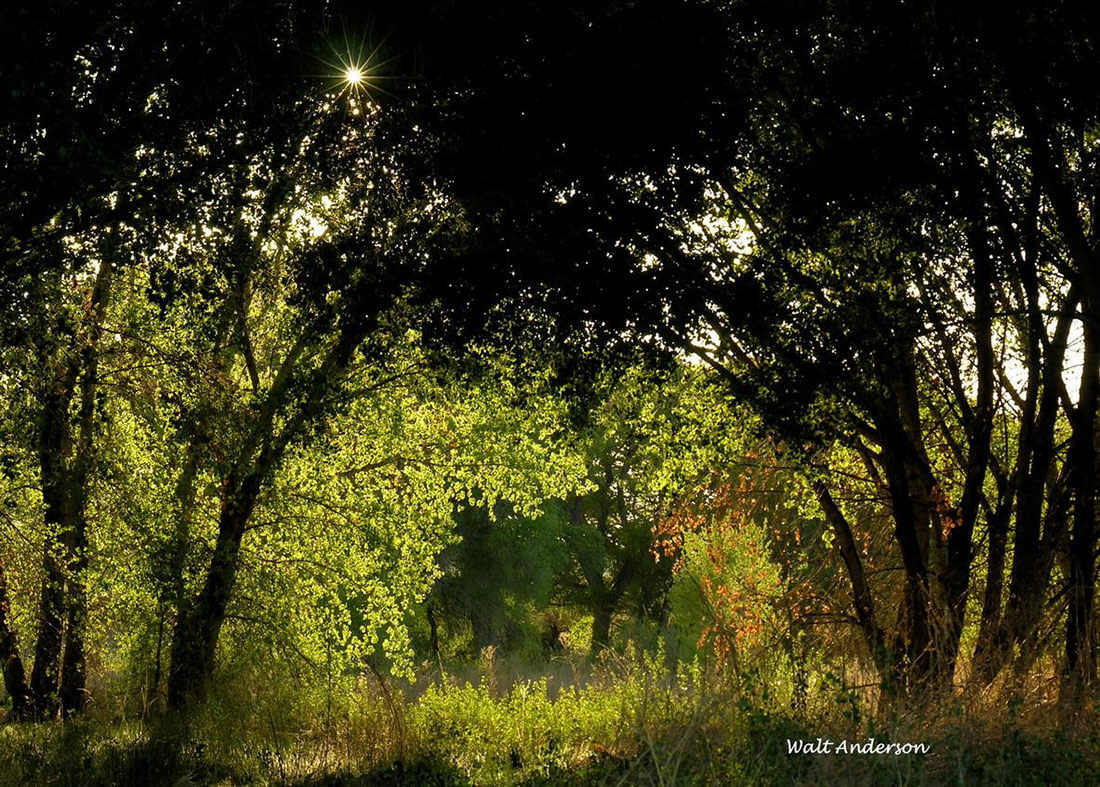

In the East, Hairy Woodpeckers also frequent the extensive deciduous forests, and I have found them in cottonwood gallery forests around Prescott’s Watson and Willow Lakes and along Granite Creek where conifers are scarce.

Invertebrates made up about 80% of the Hairy’s diet in several field studies. The bird often taps gently to detect the presence of insect tunnels, then excavates by chiseling whacks of the sharp beak. They can be important consumers of bark beetles, and their numbers can increase during beetle outbreaks. We cheer when they help control those boring beetles! They will sip sap from the shallow wells in tree bark made by sapsuckers and will occasionally fly-catch on warm, still days. They’ll take fruits and seeds when available and love both suet and peanut butter, making them popular feeder birds.

Another trait common among MOST woodpeckers is that there are two forward- and two rear-facing toes, a term called zygodactyly. However, the Hairy can shift its outer toe to the side a bit on vertical surfaces, which is technically ectropodactyly. Try using that in your next Scrabble competition! The toes are powerful with sharp claws. Notice the stiff, pointed central tail feathers that also provide support; they are attached to strong muscles around the tail bone and are not molted until other tail feathers have grown back in.

Woodpeckers fly in undulating fashion, as if on an aerial roller coaster. Here one is dropping in for a landing. It will very likely give a sharp “peek” call as it lands. There are other vocal signals, such as a rattle or whinny, that have different functions, and non-vocal drumming is common. Drumming by both sexes is multi-purpose, serving in territorial defense, courtship and mating, signals to a distant partner, response to an intruder near a nest, and (I love this) “for no apparent reason.” Most of those functions probably apply equally well to human percussionists.

As breeding season arrives, males choose a nest site and excavate a cavity. The female lays 3-7 eggs, averaging 4. Males tend to incubate and brood at night, females during the day. Nestlings are altricial—naked, blind, and weak, without any down (that’s even true for Downy Woodpeckers!). Both parents feed the young, which stay in the nest (a fairly safe site) for about four weeks. There are usually separate roosting sites that males and females occupy alone. Woodpeckers are considered primary cavity nesters—that is, they make the holes. Many other species take advantage of the holes for nesting or shelter, emphasizing the importance of woodpeckers in an ecosystem. That’s holistic thinking.

Once the young fledge, the parents subsidize them with food for a couple weeks. Here Mom feeds Junior. You can see that her primaries are brown, worn out, due for replacement. But she is a beautiful mother, and I am touched by her solicitous care for her offspring. This is her evolved duty; she is not a Harried Woodpecker.

Thanks to our bribes of suet and peanut butter, we are visited by Hairy Woodpeckers just about every day of the year. They often are joined at the food bar by Ladder-backed and Acorn Woodpeckers, as well as Northern Flickers. At the moment, these birds are doing better than many other species, but climate change can change ecosystem character quickly and unpredictably. As our pines suffer from bark beetle infestations, Hairy Woodpeckers thrive—until the pines die and decay away. Without wood, there go the woodpeckers.

I have been fortunate to see many species of woodpeckers around the globe. Nubian Woodpeckers in Tanzania inspired me to do this pastel painting. In a sense, the 224 members of this family bring some commonality to nearly everyone around the world. Our languages may differ, but woodpeckers unite us through similar shared experiences. I fervently hope that people around this finite planet will have the sense of caring that will keep woodpeckers and their ecosystems healthy. Caring requires action, so please do your part. Thanks.